Does Ross Douthat “Believe” This?

from my scratch pad

Nothing gets me so riled up as being misrepresented, and in no respect do I feel as persistently misrepresented as in my atheism. So I spend a lot of time getting miffed at conservative pundits and public moralists, and I regularly test my family’s patience with my harrumphing.

Now I will test yours re: the 2025 bestseller by Ross Douthat: Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious.

For context: I have never believed God exists beyond the human imagination. I think he’s made up.1 But I have sympathy for the human wish to feel protected and cared for and to live on after we die. And I am genuinely impressed by the complex stories and systems we have developed to make those wishes appear to come true. I don’t hate religion or its artifacts, I have no beef with believers, and I have no interest in debating my position.

But I can get lured.

I read Believe because I was intrigued by its premise, which seems to me paradoxical. Douthat is setting out to convince his readers that religion is true. Not that religion can’t hurt, not that it’s a handy way to channel our impulse for good or fulfill our need for community, not that it provides comfort regardless of its truth claims. That it’s true.

But the thing about religion, a thing he himself admits, is that it’s specific. Only one of the thousands of world religions — or maybe one small, related group of them — can be true. So the entire exercise of “thinking your way from secularism into religion, from doubt into belief,” as he puts it, seems useless (or worse) unless we can know exactly what to believe. “Religion,” as a general abstract noun, cannot be true. Only a religion can.2

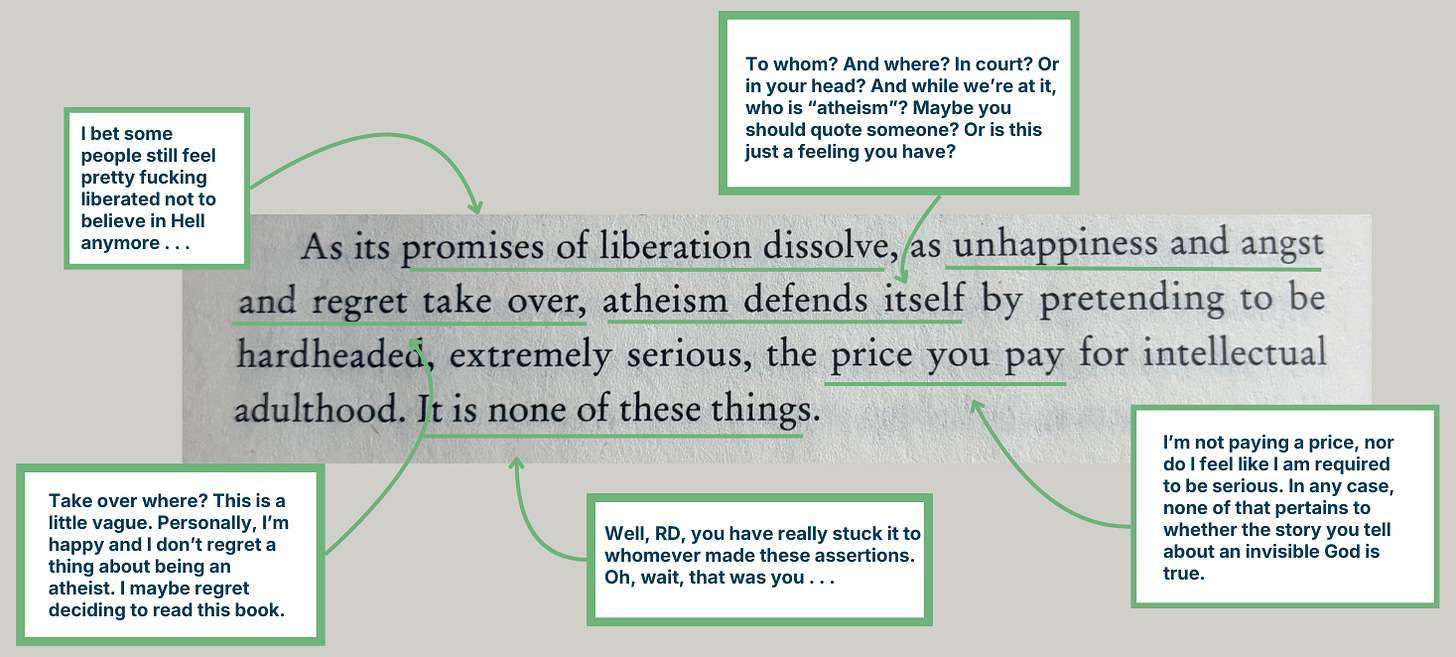

Before Douthat embarks on his quixotic quest, he takes a few potshots at me, er, atheists. Here is a rough approximation of me muttering through a paragraph:

Now imagine me reading the subsequent sentences aloud with amazement while you’re trying to read a novel or something (sorry, kids): “It is the religious perspective that asks you to bear the full weight of being human. It is the religious perspective that grounds both intellectual rigor and moral idealism. And most important, it is the religious perspective that has the better case by far for being true.” I mean (need I say?) no, no, no, and no.

But OK. Try me.

Douthat begins his argument with a call for readers to try to recover their “naïve religious self”:

I want you to imagine the world before [more or less the Enlightenment], when the burden of proof was on the skeptic, when atheism was a curiosity and supernatural belief the obvious default. Once you’re there, try to imagine or remember what made belief seem so reasonable and natural. Try to imagine yourself as a religious person untroubled by serious doubts, finding natural vindication for spiritual presumptions in the world that you encounter every day.

In other words, it would be easier to believe religion is true if you could return to a frame of mind — this imagined naïve past3 or “even [the reader’s] own childhood” — that assumes religion is true.

Well, sure, I guess it would.

As for each of his arguments, they boil down to, whatever we don’t understand, let’s call it God.

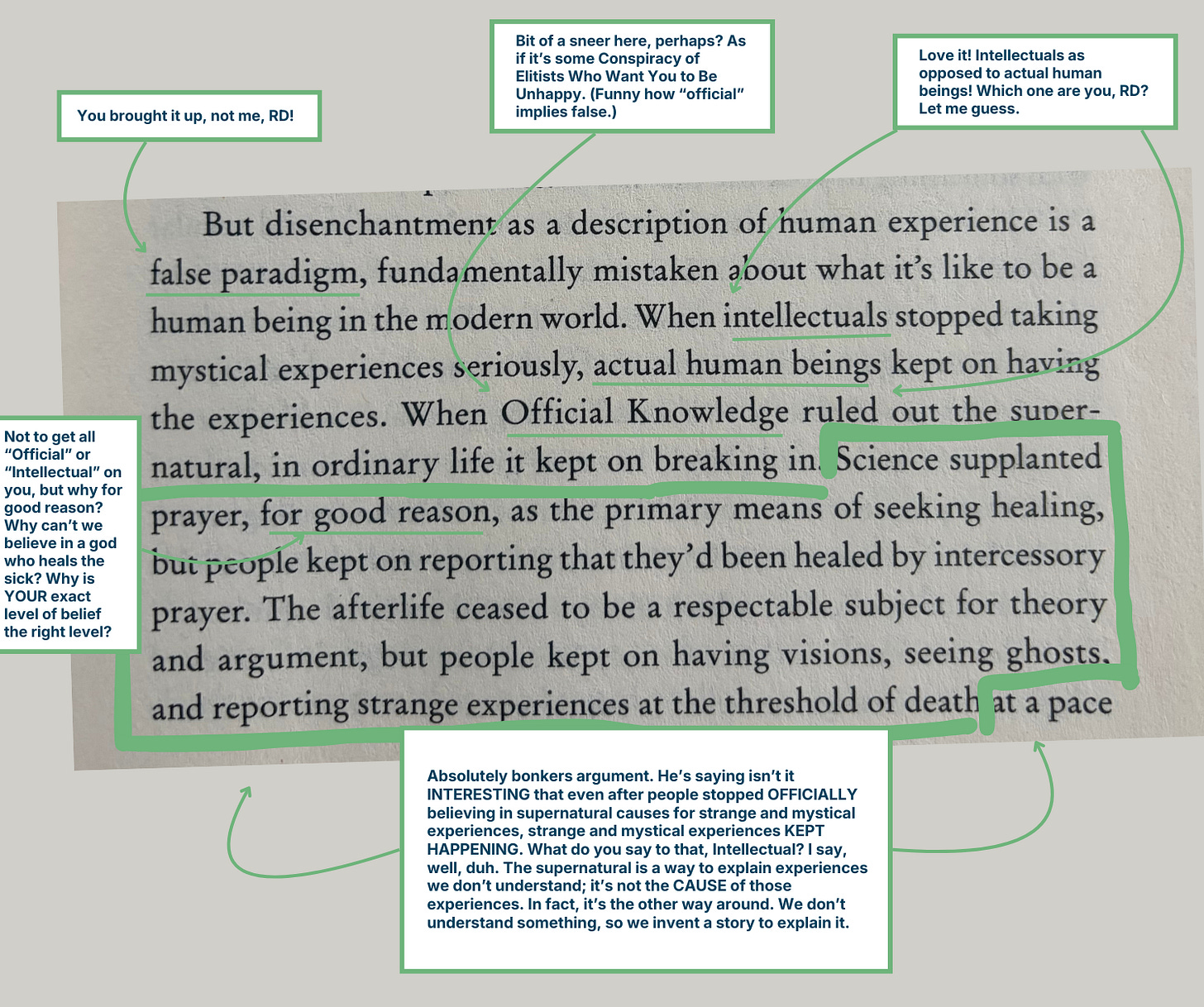

Chapter 1: The universe and its systems seem like someone made them,4 and also they’re really complicated, so therefore God. Chapter 2: Science hasn’t pinned down exactly how we feel a sense of self, or how consciousness works, so therefore God. Chapter 3: People have experiences that seem supernatural, mystical, or uncanny, so therefore God.

Each of these arguments is festooned with references and anecdotes and evidence of Douthat’s extensive reading, but all of them are undermined by a fatal lack of perspective, and what must be (he seems smart enough) a willful misunderstanding of atheism. He talks about science as if we’re at the end of it when we could be at its infancy; he talks about atheism as if it’s a bullheaded denial of human experience rather than simply a refusal to accept “God” as the answer to our natural questions and persistent needs.

We humans haven’t figured out the origin of the universe (if it has one), haven’t gotten messages from elsewhere in the universe (that we know of), still have experiences we don’t understand, still want to be important in some sort of grand scheme, still wish we didn’t have to die . . . I grant all of that. And none of it means therefore this story about an invisible supernatural being who created a universe for and is concerned with the species I happen to be a part of is true. It just doesn’t. What it means is, people really, really want to believe.5

OK, now, David Brooks, whatcha got?

In the end, Douthat acknowledges this, and in the final chapter it emerges — spoiler! — that the true one is the one he believes in.

If you, too, share the misapprehension that atheism is newfangled, please read Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World by Tim Whitmarsh.

To this point, and for sheer entertainment value, I highly recommend the video “Seth Andrews vs. God: Who Is the Better Intelligent Designer?”

At one point, discussing the Big Bang, Douthat says that there being a single moment of creation, makes it “intuitively more likely that the universe as we know it now has some specific importance to its creator” and I thought, oh dear, “intuitively more likely” — that’s your problem right there. You think your feelings and probability have something to do with one another.

Very well done! And a joy to read!

Douthat has always struck me as a extremely mediocre thinker, and Believe seems worse than his usual output. I can't bring myself to read it. I appreciate the sacrifice you made on our behalf (irony intended).

This is what I subscribed for: Thoughtful takedowns of dumb arguments. Annotation was a bonus!