Resistance Red

can a hand-knit hat really help melt ICE?

There’s a red hat in the news, and it’s not the one that’s been dominating the culture for the past 10 years, it’s not made in China, and you can’t buy it at Trump.com.

You have to make it yourself.

As I write, the hottest selling pattern on the world’s biggest knitting site, Ravelry.com, is the “Melt the ICE” hat. It’s a pointed red hat with a tassel, designed to recall the red hats worn by the Norwegian resistance during the Nazi occupation.1

A knitting store near Minneapolis2 created the pattern after the killing of Renée Good; they’re donating proceeds to immigrant aid groups. The idea is both to raise funds and to show solidarity against the city’s occupation by poorly trained, trigger-happy, terror-spreading federal troops.

The pattern has been downloaded from Ravelry 23,917 times. No, wait, 23,941.3

That’s a lot of solidarity, and it’s expanded far beyond Minnesota. The owner of CeCe’s Wool, in Guilderland, New York, told me practically everyone who comes in these days is looking for red yarn. She’s sold out of it twice, and she’s dyeing more.

If the image of a nationwide army of protesters in hand-knit hats reminds you of something other than World War II-era Norway, you’re not alone. An article in Slate suggests the caps “trigger uneasy flashbacks to the most recent time fiber arts evolved into mass protest: the pussy hat.”

It’s true: I do feel a little uneasy when I think about the Pussyhat Project, the emblem of the 2017 Women’s March and probably the best-known example of the blend of craft and activism now called “craftivism.”4 Why? I’m for handmade things — I’m for political art. So what’s the problem?

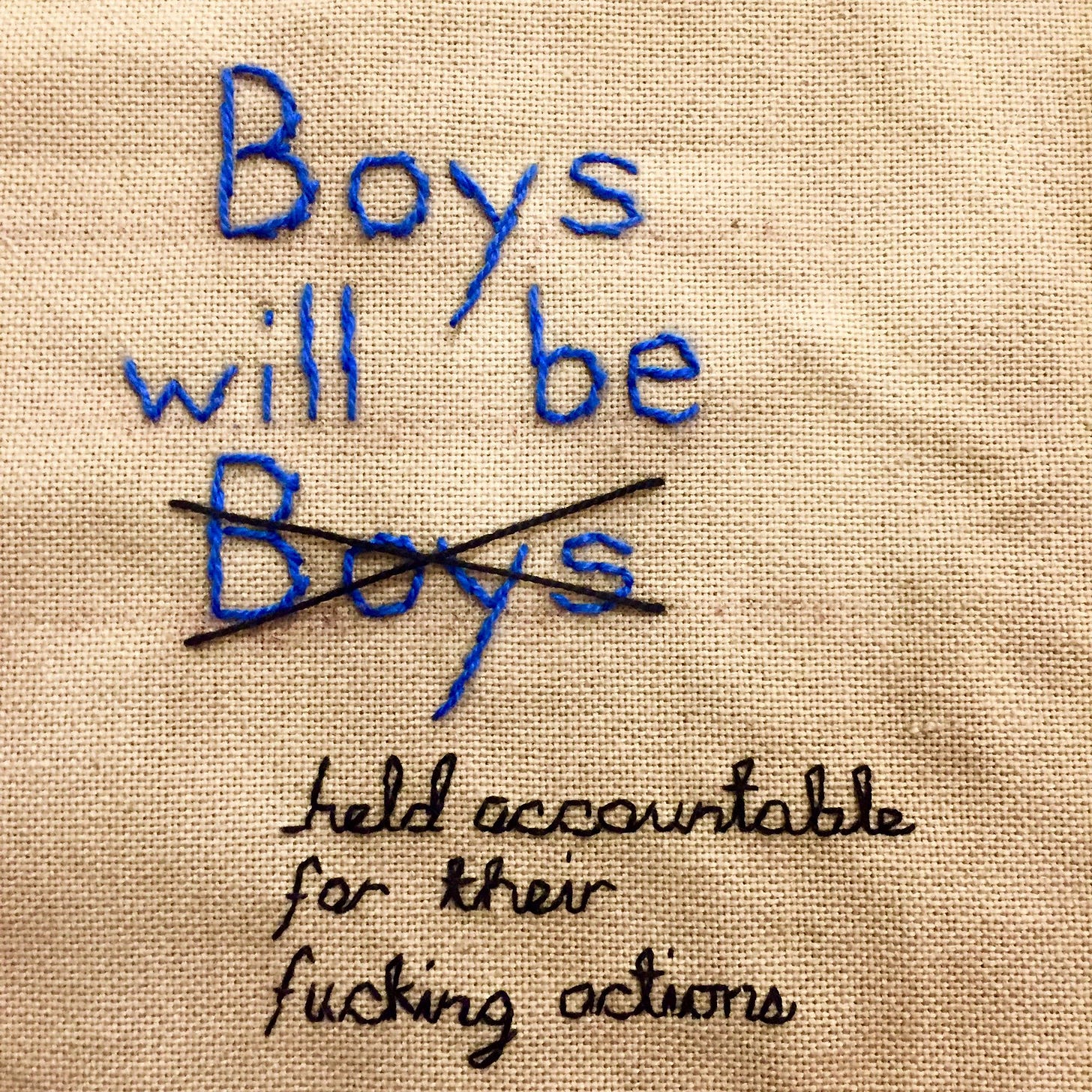

I asked Shannon Downey, the founder of Badass Cross Stitch and something of a craftivism authority. She’s a Chicago-based activist who started needlepointing when she realized that instead of “Live, Laugh, Love,” she could stitch things like (the viral sensation) “Boys Will Be Boys Held Accountable for Their Fucking Actions.”

As for those pink hats, and the red ones, too, Downey helped me pinpoint the issue: Here was a political moment “when White women of a certain age appear to be doing the very least.” They aren’t risking much — they like to knit anyway! — but they’re getting a lot of attention. And then “folks who have been living under oppression for their entire life, see this, and they’re like, Oh, great, the White ladies are making hats again.”

“So fucking valid,” she said.

“Also,” she said, “it’s totally invalid.”

First, there’s no reason to think that a person knitting a “Melt the ICE” hat doesn’t also follow ICE agents around with whistles, harangue their elected representatives, send cash to help trapped residents pay rent. And even if knitting a hat is the first political action someone has ever taken, so what? “For some people, wearing a hat out in public that says, I’m against ICE . . . that’s the most they’ve ever risked . . . That’s how you start building the muscle to take even bigger risks.”

To Downey, every novice craftivist is a potential crusader; her mission is to pull people out of their comfort zones and into the streets (metaphorically and also not).5

“I’m eager to see what could happen if craftivism shifted a smidge on the spectrum, from craft-forward to activism with a side of craft,” she writes in her 2024 book Let’s Move the Needle. That tension — between crafting as a pastime and crafting as activism — is woven throughout the book,6 which is shelved under “Handicrafts” at my library and features an embroidered title, a cheerleading tone, and step-by-step instructions for how to do needlepoint change the world.

Such Trojan-horse trickery seems entirely appropriate to craftivism, whose history features actual spies sneaking secrets into balls of yarn and using the binary (knit/purl) system to encrypt codes.7 Even when entirely aboveboard, many craftivist projects leverage an apparent duality: They use a traditional, non-threatening, female-coded hobby to express rage or dissent or even — heavens! — strongly held beliefs.

From Abolitionist “Any holder but a slaveholder” potholders in the 1800s to today’s “Fuck ICE” dish towels, the mashup of politics and, say, kitchenware is designed to raise eyebrows and attract eyeballs. At the same time, the familiarity of the domestic object serves to make the message seem less shocking, more normal, as if opposing racist tyranny were as basic to daily life as cleaning countertops.

The red hat pulls off the same trick. For a year, organizers of No Kings protests have been complaining about the lack of mainstream news coverage, but the “Melt the ICE” hat, with its cozy vibes and seeming contradictions — the pissed-off knitter, the protester armed with 200 yards of yarn — has been amply featured: The Guardian, The New York Times, NPR.

A similar mechanism may be working on participants too, drawing people to the cause through craft/craftiness. Last week, Cece’s Wool posted a video of baby lambs born on the owner’s farm. The caption begins “Of course new babies arrived in the middle of a major snowstorm and cold snap!” and moves on to, “Here’s what we are doing at CeCe’s Wool to stand with the folks in Minnesota. ICE agents executed a protester on Friday and are lying about what happened. We can’t pretend everything is fine.” Come for the cute little lambs; stay for the call to action.8

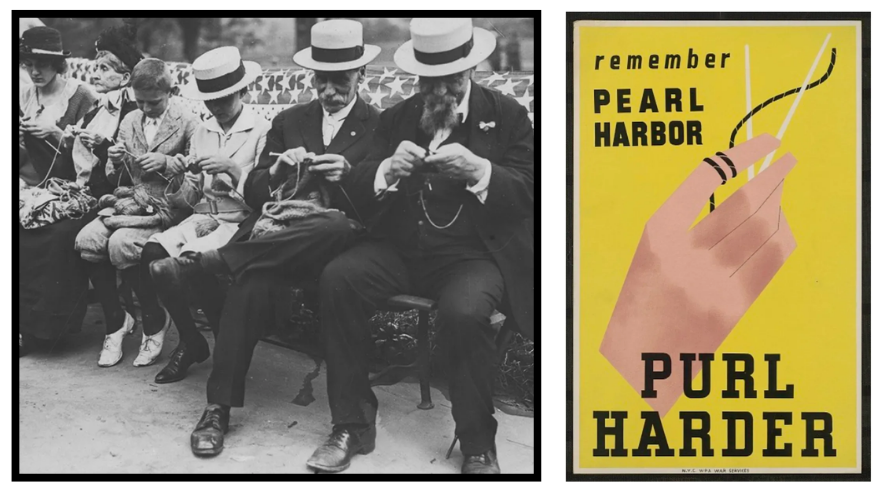

Historical accounts of craftivism cover crafting both as a medium of protest and as a means of contributing aid. In the first category would fall the AIDS Memorial Quilt, a record of grief and loss that is intimate in its detail and devastating in its expanse. In the second category are the knit-ins and wool brigades of both world wars, when knitting for soldiers overseas was considered a patriotic duty9 and propagandized as such. (“Remember Pearl Harbor? Purl Harder.”)

Underlying both kinds of craftivism is the power of scratch. What each quilt panel communicated to the beholder and each pair of socks communicated to the soldier — what each material object substantiated — was that a fellow human being cared, mind and body.

Same for the “Melt the ICE” hat.10 In addition to being a symbol of resistance, a fundraiser, and training budding activists, it’s also a thing made by a human being. People around the country are knitting them not just for themselves, but to send to Minneapolis, too. Which means someone on the front lines fighting fascism there could be wearing a hat made by a knitter here in upstate New York, just as, doubtless, soldiers on the front in World War II once did.

There are plenty of parallels between that political moment and ours, but one big difference is: I could sit here in my kitchen and order 20 warm hats for protesters, to be delivered tomorrow. But it wouldn’t be the same. A hat made by a person for another person — with their own hands, tools, skills, time, and thought, after an extra run over to CeCe’s Wool when they get red yarn back in stock — does more than keep a head warm. More for the wearer, and more for the maker too.

Shannon Downey told me that the activist community in Chicago is answering the call to knit balaclavas for Minneapolis protesters,11 and we agreed there was magic in the humanness of it, the material embodiment of care for a stranger that is the very antithesis of the ICE ethos. As she put it, “My hands made this, so your face can be protected.”

The thing that hands make, it’s precious and singular and irreplaceable, like each of us.

Our patriotic duty now, our anti-fascist mission, is to protect our neighbors and honor their humanity — and our own — in any way we can. If you’re only making a hat, “You could be doing more,” said Downey. “Do more.”

But this is a war effort. Everything counts.

Watch this to learn more about the history of the red hat in Norway. It takes a few minutes, but you will not regret it.

Needle and Skein; the pattern is by Paul S. Neary.

28,801 on Monday night, when I put this essay to bed.

The term was first used by Betsy Greer in 2003, after someone in her knitting circle said it, as she describes in Knitting for Good: A Guide to Creating Personal, Social & Political Change, Stitch by Stitch.

She’s currently teaching people how to make wheat paste to stick posters up in public places, which is, she admits, “technically kind of breaking the law.”

To read and write about craftivism is to be ensnared in a web of fiber puns. Apologies.

I don’t see why we couldn’t count the actual Trojan Horse, too.

Woke in sheep’s clothing.

In this case, the curiosity — and the press attention — often went to male knitters, such as Governor Hunt of Arizona, who knit socks for soldiers. “The Governor started his war knitting at home; once well under way, he took it to the executive offices, and those who had to see the Governor that first day were treated to the surprise of their lives.” New York Times, March 10, 1918. The surprise of their lives!

Same for the Pussyhat, which time has flattened into a few stock photos and a symbol of impotence, but which was also, I remind my snarky self, a thing, made by a person, with care.

And let’s never forget Madame LeFarge!

This has become a real thing! Red yarn was hard to find in Durham today! I ran into someone in the locally owned yarn store who had snagged the last skein of non-cotton yarn (cotton doesn't stretch so is maybe less desirable for a hat). She didn't know how to knit but was part of a group that is meeting at a coffee shop next week in hopes of learning or teaching. I hope to make it but I have a gig just beforehand! I did eventually get yarn from a chain store...